Data protection in Tunisia: a legal illusion?

This policy analysis was prepared by CIHR fellow Clément Perarnaud.

After having constitutionalised the right to data protection in 2002, and having adopted a legal act detailing its scope and setting up a national commission in charge of its enforcement in 2004, Tunisia seems to have been guaranteeing a high standard of protection for its citizens for over a decade.

But since the right to data protection has been incorporated in the Tunisian constitution, it is striking to observe that no sanction has ever been imposed for an infraction of the law on data protection.

The Ministry of Justice is expected to propose by the end of 2016 a review of the framework for the protection of personal data. In the context of future legislative debates, understanding the features and limitations of the current data protection regime seems therefore of particular relevance.

To do so, we need to first look at the actors and dynamics that allowed this legal framework to emerge in the early 2000s. At first, it does indeed seem paradoxical that the Constitution first recognized the right to data protection for all Tunisian citizens during the era of Ben Ali’s regime.

Even though it was adopted in the context of an authoritarian regime, the Tunisian data protection regime remains in place to this day, even though it was repeatedly deemed incompatible with the newly established principles of the 2014 Tunisian Constitution. This situation generates legitimate concerns on the actual effects of the consecration of the right to data protection in Tunisia.

From the unnoticed introduction of this new right during Ben Ali’s regime…

As strange as it may seem, the protection of personal data suddenly appeared on the national scene during the review of the Tunisian Constitution in 2002. Amidst relative indifference, the right to the protection of personal data was added to Article 9 of the Tunisian Constitution:

“The inviolability of the home, the confidentiality of correspondence and the protection of personal data shall be guaranteed, save in exceptional cases prescribed by law”.

Article 9 of the 1959 Tunisian Constitution (revised in 2002)

As for other dispositions introduced during the 2002 constitutional revision, this new reference to the right to data protection could be explained by the former president’s will to brighten his image in the eyes of international partners, and particularly so on the eve of the World Summit on Information Society organized in Tunis in 2005.

The constitutionalisation of the right to data protection was followed two years later by the adoption of a legal framework detailing the scope and limitations of this new right. Carried out by the Ministry of Justice, the establishment of this legal framework led to the adoption of the Organic Act n°2004-63 of July 27th 2004 on the protection of personal data.

This law, at a time the first of its kind in the Maghreb region, established the data protection regime that is still in place in Tunisia, and placed it under the supervision of the newly created “National Authority for Protection of Personal Data (INPDP)”. After the adoption of application decrees in 2007 and the designation of its members in 2008, this institution quietly took office in 2009, more than six years after the constitutionalisation of the right to data protection.

… to the consecration of this right in the Tunisian Constitution of 2014

Following the fall of Ben Ali’s regime in 2011, the new Tunisian Constitution in 2014 broadened the right to data protection in Article 24. As part of this Article, the right to privacy was added to the rights protected by the Constitution, reinforcing indirectly the right to data protection.

The state protects the right to privacy and the inviolability of the home, and the confidentiality of correspondence, communications, and personal information.

Article 24 of the 2014 Constitution

More generally, the adoption of the 2014 Tunisian Constitution constitutes a fundamental legal shift, particularly in light of Article 49, that imposes the proportionality of the restrictions exercised on the rights and freedoms guaranteed to all citizens.

Despite these significant constitutional changes, the 2004 Organic Act on the protection of personal data instituted during the Ben Ali regime was left intact.

A data protection regime inefficient by design

In many aspects, the legal framework regulating the protection of personal data in Tunisia shares the same weaknesses of Ben Ali’s regime that eventually led to its fall.

By paying lip service to human rights rather than properly protecting and enforcing the rights and freedoms of the Tunisian citizens, the 2004 Organic Act on the protection of personal data echoes the numerous public declarations of the Tunisian president with regards to human rights.

At first sight, the 2004 Organic Act seems to set a high standard of protection for Tunisian citizens. Indeed, the Tunisian data protection regime is based on the principles of lawfulness, processing and accountability. It gives rights to those individuals whose data is processed, and sets out obligations for the organizations and individuals in charge of the processing. As a general rule, personal data processing must be either declared by the processors or previously authorized by the INPDP.

But the Tunisian data protection regime is significantly weakened by the numerous exemptions it gives to certain data processors. Indeed, organisations with a “public personality” (such as police stations, tribunals and universities) fall out of the scope of the legislation and are not bound by the obligations that would normally apply to personal data processors in Tunisia. Public organisations do not have to declare data processing and therefore deprive individuals of the possibility to exercise their rights of access, rectification and opposition, as well as to express their informed consent. Employers also benefit from a derogatory regime with regards to the processing of the personal data of their employees.

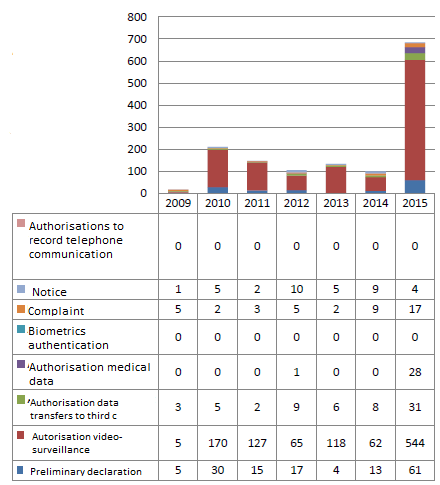

The great discrepancy between the law text and its actual application is also a major hurdle preventing Tunisian citizens from effectively exercising their right to data protection. The National Authority for Protection of Personal Data (INPDP) is the main institution in charge of the control and enforcement of the legal framework on data protection. The recent statistics published by the INPDP on its activities during the period 2009-2015 clearly indicate how rarely the law was respected by data processors until recently.

Until 2015, rare were the data processors (such as private companies) engaging with the INPDP in order to declare their own processing of personal data in accordance with the law. As a result, the application of the 2004 Organic Act has been for years more exceptional than systematic.

This discrepancy can be explained firstly by the very limited resources at the disposal of the INPDP to ensure a proper enforcement of the rules. Furthermore, the composition of the INPDP may also have undermined its efficiency. For instance, its two first presidents from 2009 to 2014 were former magistrates. Their professional background may have prevented them from acting proactively when conducting communication campaigns and making use of public “name-and-shame” strategies. In line with the normal working practices of the jurisdiction, they only considered cases when seized by a third party.

It is against these habits that Chawki Gaddes, the new president of INPDP since 2015, has been trying to fight since his nomination. The recent increase of cases examined by the INPDP in 2015 tends to indicate that his efforts have already been rewarded. According to him, the most important task on INPDP’s agenda now is the revision of the 2004 Organic Act, in order to ensure the compatibility of the data protection regime with the new Tunisian Constitution and with international standards.

Towards a reform of the Tunisian data protection regime

The reasoning behind the future revision of the data protection regime is twofold. First, it appears increasingly needed to review laws adopted in the context of Ben Ali’s authoritarian regime, in order to avoid discrepancies with the new Tunisian constitution. For instance, the state’s exemptions from general obligations with regard to personal data processing cannot be seen as compatible with the essence of Article 49 and should therefore be promptly reviewed.

Secondly, at the international level, it must be noted that Tunisia is currently not considered by the European Union as a country providing an adequate level of protection by reason of its domestic law or of the international commitments it has entered into. Nevertheless in 2015 Tunisia and the European Union launched negotiations for a Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area, encompassing not only trade in goods but also in services and in a range of regulatory areas. The compatibility of Tunisian and European laws in certain sectors has thus progressively become a priority for the Tunisian government.

The alignment of the Tunisian data protection regime with European standards is becoming more and more needed. It is in light of this reality that one can understand the request of Tunisia to accede the Convention 108 of the Council of Europe in 2015. The Convention 108 for the Protection of Individuals with regard to Automatic Processing of Personal Data is still today the only binding international treaty in this field.

Non-compliance to international standards on data protection and privacy could affect Tunisian businesses on the long-term. The stark increase of data transfers between Tunisia and Europe, fuelled by the rapid development of the IT off-shoring industry in Tunisia, is therefore a strong incentive in favour of the review of the current Tunisian data protection regime.

Unlike the General data protection reform in the European Union, the future revision of the Tunisian data protection regime has not yet generated a strong interest from the private sector and from civil society organizations. To date, the level of engagement between the Tunisian government and all relevant stakeholders has actually been very low on these issues. Yet it is only by engaging them in this process, and most importantly of all, informing them about what is really at stake, that the Tunisian government will prevent the new data protection regime from becoming a new legal empty shell.

Read more CIHR publications.